'Across the Spider-Verse,' Against the Hero’s Journey

How 'Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse' rejects Joseph Campbell's monomyth.

This post was originally published on June 5, 2023. AFD has since switched platforms, and for technical reasons, this post didn’t port over. Since Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse received three Golden Globe nominations yesterday, this seemed like a good time to re-publish it. It contains spoilers for Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. Enjoy!

You probably don't need me to tell you to go see Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. For one thing, the opening weekend box office suggests that you've seen it already. For another thing, it's getting rave reviews from, well, everyone, which means at this point, roughly 96 hours after the movie's release, I would only be adding to an already-massive chorus if I told you that the animation is spectacular, the voice acting is top-notch, and that the story is exciting and funny and moving and all the things for which Nicole Kidman tells us we go to the movies in the first place. So I'm not gonna talk about any of that.

What I would like to talk about, because thus far I've seen surprisingly little discussion about it online, is the way the movie gives big middle finger to the concept of the hero's journey, sometimes known as the monomyth.

For those of you who have somehow managed to avoid it thus far, the hero's journey/monomyth is a concept which takes note of structural and archetypal similarities between many (some would incorrectly say "all") stories as a means of basically saying, "Hey, isn't it interesting that there's this recurring format amongst popular myths in various different cultures." It was popularized by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, in which the author describes the idea thusly:

"A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man."

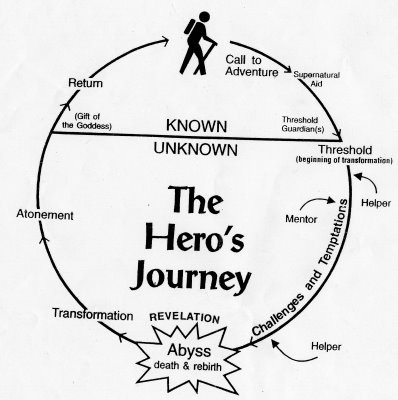

And here's what it looks like as an illustration. Some version of this appears in almost every popular elementary screenwriting book out there today:

Campbell presented the monomyth as a scholarly observation to be considered and discussed, not as a template for storytellers to utilize over and over and over again. Problem is, following the success of Star Wars in 1977, writer/director/producer George Lucas spent several decades telling anyone would listen that his movie was deliberately modeled on the monomyth, because his goal the entire time was to create a new mythology for young people. Studio executives heard Lucas' claim as "There's a formula for making movies that gross a gajillion dollars." And that's when screenwriting instructors started handing out charts like the one above, and pretty soon, the hero's journey did become a template for storytellers to utilize endlessly.

Which brings us to Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse.

A sequel to 2018's Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, Across the Spider-Verse once again follows protagonist Miles Morales (Shameik Moore) as he struggles with the duties and consequences of his newly-acquired superpowers. Morales is a fairly recent addition to Marvel Comics lore, created by writer Brian Michael Bendis and artist Sara Pichelli in 2011. Although in some ways he's similar to the original Spider-Man, Peter Parker, in other ways, he's definitely not - the most obvious of those differences being that Miles is biracial. Appropriately, then, during the course of Into the Spider-Verse, Miles ultimately learns to be his own Spider-Man after multiple attempts to basically just be Peter Parker 2.0.

Across the Spider-Verse deepens and broadens this theme by taking on the very notion of the monomyth. Although the villain of the story, technically speaking, is the Spot (Jason Schwartzman), the primary antagonist is really Miguel O'Hara (Oscar Isaac), the Spider-Man of 2099. Miguel is brooding, grouchy, and hyper-focused on his mission, a character much more akin to Batman than traditional depictions of Spider-Man. He has the technology to freely traverse the multi-verse, and he has come believe that there's a "canon" - certain key tragedies through which all iterations of Spider-Man, in every single different reality, must suffer. These include the death of both a beloved uncle and a police captain close to the Spider-Man in question. Miguel asserts that should these events not happen - should anyone travel to any reality and interfere - the reality in question will unravel, and everyone in it will perish.

On top of that, Miguel strongly dislikes Miles because Miles, he asserts, is the "original anomaly": The radioactive spider that gave Miles his powers was from another reality, and was supposed to bite that reality's Peter Parker. Since it bit Miles instead, Miles became Spider-Man, another reality was denied its own protector, the Peter Parker in Miles' universe was killed, and the climactic events of the original Spider-Verse led to the creation of the Spot. In other words, Miguel considers everything that happens in these two movies to be Miles' fault.

Worse still, while the police captain who dies is usually the father of Gwen Stacy, in Miles' reality, it's going to be Miles' dad (Brian Tyree Henry) - and Miguel expects Miles to sit by and allow that to happen, because it's canon. "You can save one person," he tells Miles, "or you can save everyone."

It's clear that returning writer/producers Phil Lord and Christopher Miller (collaborating this time with writer Dave Callaham and directors Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, and Justin K. Thompson) are dealing with the idea of the monomyth from the moment Miguel first uses the word "canon." This, my fellow nerds are already aware, is the term all geeks use to describe in-universe story continuity that "counts." Go to a comic book convention, and you'll hear endless arguing about what is or is not canon, and how much that matters. It's a phenomenon that's fairly unique to sci-fi and fantasy, where realities can change on a dime, and maybe even comics in particular, because there have been so many different iterations of these characters over the decades that there is room to dispute what did or did not actually happen. It's intended to codify all these different events into one coherent story.

But what it often actually does is punish creativity.

For one thing, since so many of the protagonists Campbell discusses are religious figures, it has rendered the true Everyman unimportant in genre narrative; now the protagonist must always a messianic Chosen One who was divinely fated to save the world (John Connor, Neo, Bran Stark, Harry Potter, Zack Snyder's version of Superman, etc.).

For another thing, one of the most fun aspects about these icons is that so many different writers and artists can come along and do so many different things with them. They're like campfire stories, with people constantly coming along and adding their own flourishes, if not outright making changes. It's part of what keeps these stories fresh, and it allows us to give thought to what makes these characters these characters.

The canon-conscious, like Miguel, believes that there is a way the story "must" go to be "correct," and they're not the least bit interested in even exploring what may lay beyond those very strict boundaries. If it were up to them, characters like Miles Morales probably wouldn't exist (indeed, plenty of right-leaning readers were not happy when Morales was first introduced).

They want a monomyth.

This motif is illustrated visually, when Miguel shows Miles an endless array of Spider-Men holding dying loved ones in the arms; in a college advisor's insistence that Miguel exploit stereotypes about his race for admissions essays; in Miguel's refusal to speak to Miles in Spanish, symbolically rejecting his own "otherness" while conforming to toxic fandom's need for Spider-Man to be white; and in the subplot conflicts of other characters - particularly Spider-Gwen (Hailee Steinfeld), a version of Gwen Stacy that has spider-powers of her own. She rejects Miles' romantic advances because "In every reality, Gwen Stacy falls for Spider-Man, and in every reality, it ends badly." Not only that, but she is, in fact, going to allow her father to die because it's what is "meant" to happen. She has surrendered herself to the monomyth.

Miles, of course, is not so compliant. "Everyone keeps telling me how my story is supposed to go," he tells Miguel during a climactic fight. "Nah. I'm'a do my own thing." A "mistake" - i.e., definitely not the Chosen One - Miles renounces the hero's journey, and escapes to go try and save his father. He is now, truly, unique and unbound by the rules - both of Miguel, but also of storytelling as it's been taught for at least the past forty years.

It seems like the biggest audience complaint about Across the Spider-Verse has been that it ends on a cliffhanger (the conclusion, Spider-Man: Beyond the Spider-Verse, is due in March 2024). And, hey, I'm a realist - the decision to conclude the movie this way must have been, at least in part, a financial one. But given its repudiation of hero's journey, it also makes sense that this movie would have an unusual structure (which it does - not only does it end on a cliffhanger, but it opens with a lengthy prologue into which Miles doesn't figure at all). I would not be the least bit surprised if Lord and Miller continued to mess with the monomyth and traditional story structure in Beyond the Spider-Verse.