Challenged by 'Challengers'

Luca Guadagnino's new engaging new melodrama stumbles at the end.

There’s a scene early in Challengers where one character asserts that he’d allow another character to fuck him with a tennis racket. Because the movie is directed by Luca Guadagnino, who famously had Timothée Chalamet fuck a peach in Call Me by Your Name, it occurred to me that this might actually be foreshadowing for the most interesting sex scene of 2024.

For better or worse, there is no sex with an inanimate object in Challengers… although there is plenty of sex between human beings. Challengers chronicles a 13-year-long romantic triangle and tennis rivalry, and for most of its 131 minutes, it works as a highly engaging melodrama, the cinematic equivalent of juicy office gossip: you will genuinely wanna know who wins on the court and, more importantly, in the matters of the heart. Unfortunately, not unlike Abigail, the movie stumbles near the end, when the narrative becomes needlessly convoluted as part of what I think must be a bid to inject the story with extra profundity. It’s kind of like tuning in to the final episode of a reality dating show only to find the remaining contestants suddenly speaking in Pig Latin for no discernible reason.

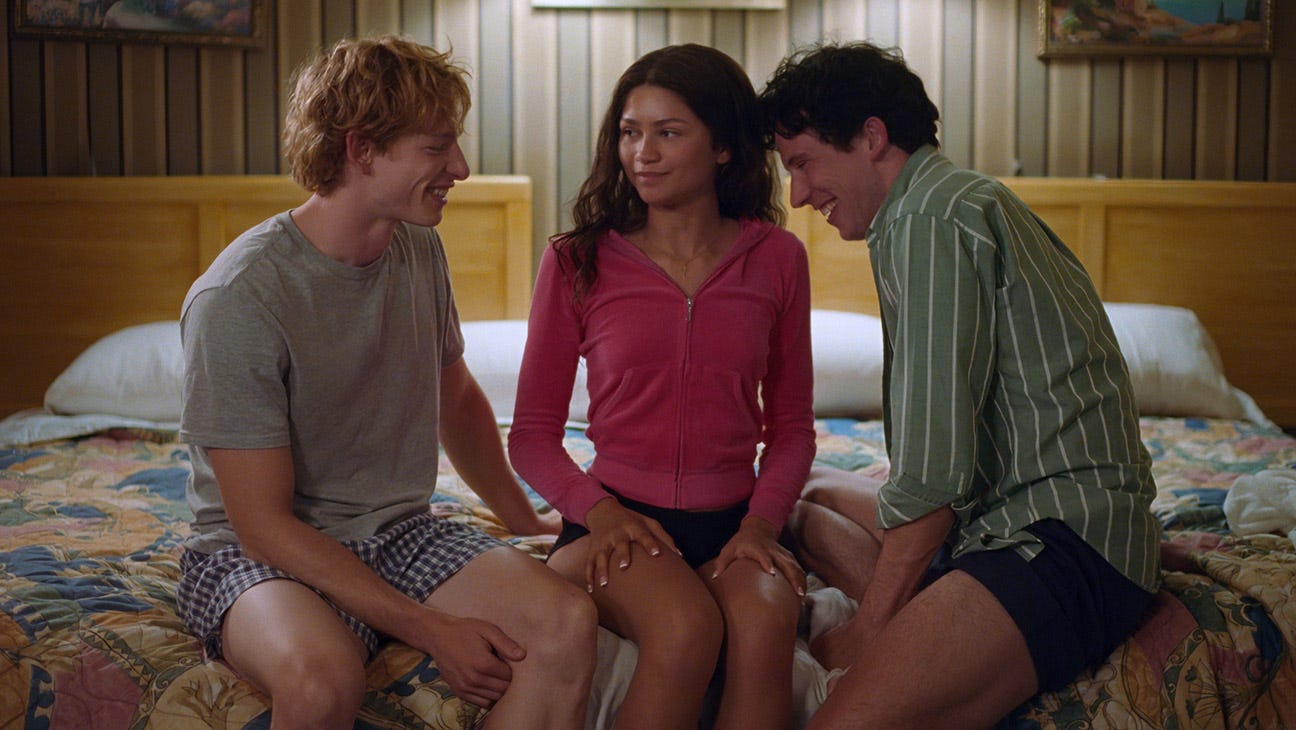

Challengers begins at a 2019 tennis tournament, where Tashi Duncan (Zendaya) closely watches a heated finals match between Patrick Zweig (Josh O’Connor) and her husband, Art Donaldson (Mike Faist), who she also happens to coach. The movie then begins to leap between the past, when these three first became entangled, and the present, when their conflict has reached its zenith.

Patrick and Art, we learn, were close childhood friends, doubles partners, and occasionally singles opponents, known as “Fire and Ice” because of their contrasting personalities (when Art comments that Tashi is “an incredible young woman,” Patrick makes the joke about intercourse with a racket); Tashi, was an 18-year-old phenom, already on the path to Serena Williams-esque superstardom. They meet at an industry event, where Art and Patrick both make their play for Tashi.

That winds up being Patrick, and while Art claims he’s not upset about it, evidence strongly suggests otherwise: he is, in fact, a manipulative snake, who goes about trying to quietly Iago a breakup between the two. Not that you exactly feel bad for Patrick, who is more than a little immature (did I mention he floated the idea of fornicating with a tennis racket?).

Eventually, Tashi and Patrick have a huge fight right before an important match, during which Tashi suffers a career-ending injury, and it’s Art who stays by her side throughout the ordeal, eventually earning his position as her new romantic partner. Eventually, they get married and have a daughter, Lily, and by the time they cross paths with Patrick again in 2019, he’s broke and washed up, while Art has all but achieved Andre Agassi status. They only wind up playing one another at a rink-a-dink tournament because Art requires some easy, confidence-boosting wins before going to the U.S. Open… but needless to say, their long history renders the match infinitely more complex and, er, challenging (sorry).

Let me emphasize again that, purely as a soap opera, Challengers is excellent. Guadagnino’s direction is characteristically assured, even if Challengers seems less weighty than his other films. The pounding electronic score, by Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, is comedically overbearing and sometimes so out of place it’s almost like watching a Baz Luhrmann movie; in these moments, Guadagnino seems to have no higher aspiration than to keep us entertained, which he does, and then some.

The characters, meanwhile, are all multi-faceted enough (the screenplay is by Justin Kuritzkes), and the performances are so on-point, that you get sucked into what is, for all intents and purposes, a fairly low-stakes story about rich and famous children in lust. The movie has no significant characters outside of the three leads, so obviously a weak link in the chain would be a major issue - but they all completely nail it. Zendaya, who between this and Dune: Part Two is already having another momentous year, is especially great; come to think of it, Tashi is not entirely dissimilar from Chani in Dune, in that she’s a total badass who is also capable of being deeply warm and loving. If I’m hesitant to say this is the best performance of her career thus far, it’s only because I’ve still never seen Euphoria.

There are hints of greater meaning as well, via the clear, compelling theme of both personal and professional identity that runs throughout Challengers; these characters are both vaguely confused about who they actually are as people (they repeatedly joke about whether or not they can do anything other than “hit a ball with a racket”) and who they earnestly want to schtup (Art and Patrick constantly and aggressively munch on decidedly phallic-looking foods, often while looking deep into one another’s eyes, smiles plastered across their faces). Challengers isn’t a coming-of-age story - the characters are too old for that - but it is a story about people struggling with who they are as their youth truly comes to its conclusion. These characters may only be in their early 30s, but as professional athletes, that means it’s time for their careers to start winding down… and since those careers began when they were children, they’re all these people have ever known. This little bit of extra heft is part of what makes Challengers so captivating.

But I couldn’t tell you what the point of Challengers is - or what Guadagnino thinks the point of Challengers is. It becomes exhausting as it nears its conclusion, right when it should be at its most magnetic. The script piles too many events and reveals right on top of one another, and is perhaps too overly confident in its ability to convey a message via vague subtext. I suspect Guadagnino knows this is a problem, too, because the final tennis match is shot in a hyper-stylized manner that substitutes incoherency for excitement, Michael Bay-style: sure, the camera assuming the P.O.V. of the tennis ball sounds cool, but it ends up being a mishmash of incomprehensible images and the aforementioned cacophony of Reznor and Ross’ score. Challengers needs a simpler, or at least more transparent, finale, something as involving and Jerry Springer-ready as everything that has come before it. Instead, it turns into the MTV version of one of Guadagnino’s other movies, which generally do a better job earning their end-of-narrative ambiguity. The challenge of Challengers is that it aspires to be something more than “just” a good story, and in so doing, winds up being a pretty-okay story.