The Class of 1999: 'The Blair Witch Project'

This movie didn't invent the found footage subgenre, but it sure did popularize it.

1999 was a historically-great year for film and dramatic narrative as a whole. I’m using my 2024 to look back at, reconsider, and celebrate these stories as they all celebrate their 25th anniversaries. Join me, won’t you?

The Blair Witch Project - written and directed by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez - January 23, 1999

The Blair Witch Project is to the found footage horror movie what Nine Inch Nails was to industrial music: it didn’t originate the genre, but it sure did popularize it.

I think at this point everyone more or less knows the premise of The Blair Witch Project, but just in case, the movie’s opening block of text sums it up nicely:

“In October of 1994, three student filmmakers disappeared in the woods near Burkittsville, Maryland while shooting a documentary.

“A year later, their footage was found.”

So the film you’re watching purports to be that found footage (thus the name of the subgenre). It’s a fairly brilliant way to make a no-budget scary movie, because, if executed correctly, it makes outlandish concepts feel plausible, and it doesn’t matter that it looks cheap. The conceit goes back at least as far as Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust in 1980, if not farther. But it still seemed like a novel gimmick in 1999, because, as it turns out, making a sickeningly-graphic movie called Cannibal Holocaust isn’t a surefire path into mainstream consciousness. And I think other pre-Blair Witch entries in the genre, like The McPherson Tape (1989) and The Last Broadcast (1998), simply never had the promotional backing to make the world at large aware of them.

But The Blair Witch Project, initially made on a budget of just $35,000, was fortunate enough to both debut and be wildly well-received at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival, where it was purchased by the now-defunct Artisan Entertainment for a cool $1.1 million. Artisan had the money to do a little extra post-production work to make the movie fit for mass audiences and the muscle to give it a wide release and make sure people knew about it (the stars were on the cover of Newsweek, the directors were on the cover of Time), while Sundance gave it an air of respectability. On top of that, it was one of the first movies (if not the first movie) to ever have a viral marketing campaign, including a sizable amount of web component. Thus, The Blair Witch Project was an immediate hit, ultimately grossing $248 million worldwide, spawning two (vastly inferior) sequels, and propelling found footage’s popularity into the stratosphere, to the point where it seems like there’s a new one every week now.

The Blair Witch Project’s success at Sundance was obviously the best thing that could have possibly happened for it in terms of getting eyeballs and making money - but, paradoxically, it was the worst thing that could have happened for it in terms of being well-received by general audiences. By the time Artisan released the movie in July, it had been overhyped to its own detriment; audiences had been told for months that it was the next The Exorcist, when it was really just a solid little flick. Consequently, while The Blair Witch Project was supposed to be THE horror movie of that year, by the end of the summer, the horror movie people were ACTUALLY raving about was a film that arrived with almost no buzz, The Sixth Sense.

It’s easy to see how much more effective The Blair Witch Project would have been for unsuspecting audiences than it was for audiences who’d been bombarded with endless hype about the movie for six months. Nobody had ever heard of co-directors/co-writers Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, nobody had ever heard of stars Heather Donahue, Joshua Leonard, or Michael Williams (all of whom use their real names in the movie), most people were unfamiliar with “found footage” as a concept, and, apparently, a lot of people thought it was a real documentary (this was just months after Google launched, when looking stuff up was a far more complicated process). For the crowd at Sundance, then, seeing The Blair Witch Project for the first time was like hearing Orson Welles read War of the Worlds on the radio.

If nothing else, that’s a testament to the fact that The Blair Witch Project feels fairly real. Myrick and Sánchez taught their trio of actors how to use the film equipment, sent them out into the woods, and then basically orchestrated scary shit from off-camera, generally without giving the cast a heads-up first. So there was no script, really, and the fact that the whole movie is more or less improvised goes a long way towards giving it that oh-so-important sense of verisimilitude.

Also helpful in that regard is the fact that you never really see anything - including the Blair Witch (neé Elly Kedward) herself - which is always an effective means of scaring people regardless (see: Jaws, Alien, Se7en), but in this case also means the audience never has to try and wrap their head around something truly inexplicable, like a UFO or a kaiju (another likely reason the movie fooled Sundance audiences). The movie’s scares come from relatively small, not-especially-far-fetched occurrences - a small pile of rocks appearing outside a character’s tent in the morning, distant sounds in the night, inexplicable twig figurines hanging from the trees - that, were you to personally experience them during a camping expedition, would 100% creep the shit out of you, guaranteed.

Appropriately, the film’s character development is thus limited to things three young people in this situation would reasonably say to one another in the course of experiencing the ordeal. Exposition is limited to their documentary interviews from local townspeople; what we learn about the characters we learn almost entirely through their actions. I suppose there might have been a way to have the trio sit around the hotel their first night and swap backstories, but that probably would have broken the illusion - so we don’t learn, for example, that Josh has a serious girlfriend until they’ve been lost in the woods for a couple of days already, and he reassures the others that she’ll be looking for him and will thus call for help. The Blair Witch Project certainly adheres to the Law of Show, Don’t Tell.

In fact, I would argue that the movie’s most fantastical element is the one that also immediately gives away that it’s not real: there is no way in pluperfect hell that this footage was shot by student filmmakers. Student filmmakers would never make anything that looks this shitty.

Indeed, one of audiences’ biggest complaints about The Blair Witch Project is that it’s a LOT of shaky cam of the ground, to such a degree that some viewers felt nauseous. But even the earlier parts of the movie, before the trio are meant to be scared, when they’re just filming stuff for their documentary, look awful. They give so little thought to framing that it’s almost as though they’ve never actually seen a movie before, let alone study the medium. Maybe we’re meant to believe these are bad student filmmakers? (And this is to say nothing of the fact that using different styles for when the characters are calm and when they’re bugging out would have been a good way to convey their internal feelings visually and heighten the audience’s feeling of anxiety.)

In any case, I don’t think the fact that the movie looks bad is its problem. Nor do I believe that its problem is making the audience feel shortchanged by truly showing them nothing (whereas the aforementioned Jaws and Alien DO show you their respective monsters, even if fleetingly).

I think The Blair Witch Project has two primary issues.

The first is that while it’s great the movie avoids heavy-handed backstory, the characters don’t quite pass muster against the Adjective Test. I don’t really know the difference between Josh and Mike, other than Mike seems quieter. The trio do feel like real people, but they don’t feel like especially interesting people.

The second issue, which is arguably even more of a weakness than the first, is that The Blair Witch Project has no story. And whether audiences were conscious of it not, that’s the reason they felt shortchanged when the film was over.

Oh, make no mistake: The Blair Witch Project has a PLOT. But plot and story are two different things. I hate to sound like a broken record, but stories have a point - the narrative coheres around and explores a central theme or themes, thereby enabling the storyteller to say something larger about life.

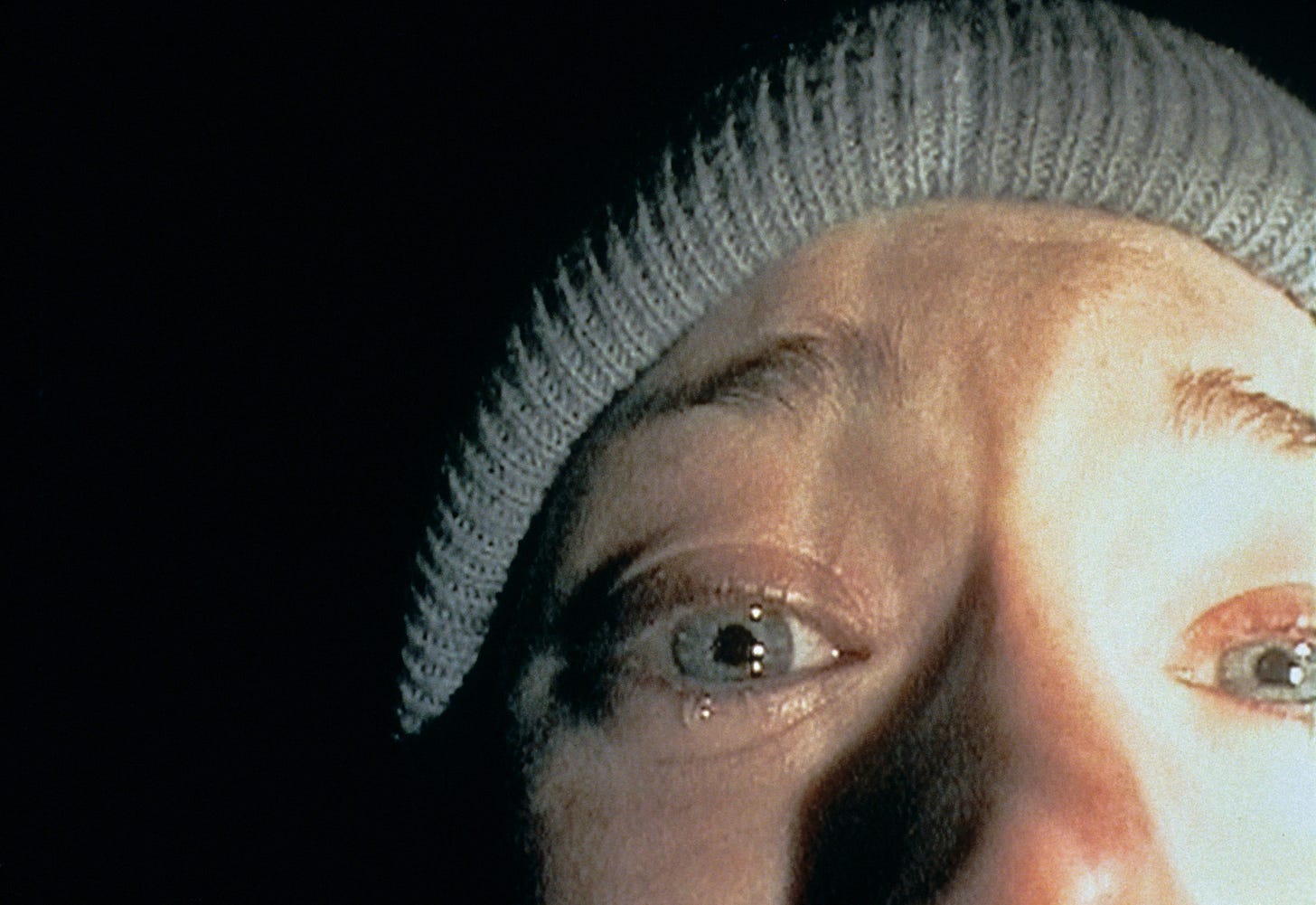

The Blair Witch Project does not cohere around a central theme or themes, and it doesn’t have anything larger to say about life. It pays lip service to being about hubris, kind of, in Heather’s infamous monologue late in the movie, when she’s filming herself crying…

…except Heather, though often annoying, doesn’t really seem that hubristic; her project is not ill-advised or inherently dangerous. One - ONE - of the people they interview for their documentary says “You kids will never learn,” meaning they shouldn’t pursue the Blair Witch - but it’s not exactly Crazy Ralph from Friday the 13th, who literally tells the characters they will die if they go Camp Crystal Lake. Even the lady who claims to have seen the Blair Witch doesn’t warn them to stay out of the woods. The things that Heather lists as her own crimes - “I insisted we weren’t lost. I insisted we keep going. I insisted that we walk south.” - are not really crimes, because they’ve clearly been manipulated by the Blair Witch the whole time. They could have walked in any direction and they would never have found their way out of those woods.

The other argument one could make is that The Blair Witch Project is a movie about movies… but, again, it only briefly engages with that theme, as when Josh tells Heather that looking through the viewfinder distorts reality, or when Heather admits she’s still filming their ordeal because “It’s all I have left!” It’s still not really saying anything meaningful about film; mostly, I think Myrick and Sánchez decided to make the characters documentarians because it made both their possession of film equipment and their instinct to constantly run the camera even at inopportune times feel less improbable.

The Blair Witch Project is not generally considered to be part of the “torture porn” subgenre of horror, because its violence is not explicit. But I’d argue that because it has no meaning, no purpose beyond being scary, it is torture porn. The three leads sell their desperation; you feel for them as the days go by and they can’t find their way out of the woods and they’re hungry and tired and scared (even if there was no supernatural element, The Blair Witch Project would be harrowing). But ALL you’re doing is watching these characters suffer, and you KNOW that they’re all going to die. The Blair Witch Project’s entertainment value derives solely from the excruciating calamity the characters experience. It seems to me that’s the very definition of “torture porn.”

But I tell ya what: I don’t think anyone ought to hate The Blair Witch Project. Yes, there have been a LOT of bad found footage horror movies in the years since, some which even made a lot of money… but there have been a LOT of bad every kind of movie in the years since, some which even made a lot of money. The found footage subgenre itself is not inherently awful, as proven by films like Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon, The Visit, The Last Exorcism, Lake Mungo, the V/H/S anthology series, Host, and even some non-horror movies like Chronicle and End of Watch. Those movies most likely wouldn’t exist without The Blair Witch Project. A quarter of a century after its release, The Blair Witch Project’s legacy may be stronger than the film itself… but then, most films will never make this kind of impact, period. Myrick and Sánchez didn’t go on to become big-deal directors, but they certainly made one of film history’s most influential debuts.