'The Substance' Is Droll, Disgusting, and Disturbing

To call The Substance outrageous would be to undersell it. If most movies start at a single-digit level of volume before gradually growing louder, writer/director Coralie Fargeat’s pitch-black body horror/satire starts at an 11 and ends as a cacophony. It is the fleshy pulp that results from obliterating Kubrick, Cronenberg, De Palma, Carpenter, Lynch, Gilliam, Aronofsky, Serling, and Aesop in a blender. It is a monster, something so primordial and freakish that its very existence simultaneously inspires awe and negates the possibility of a benevolent God.

In case you can’t tell, I loved it.

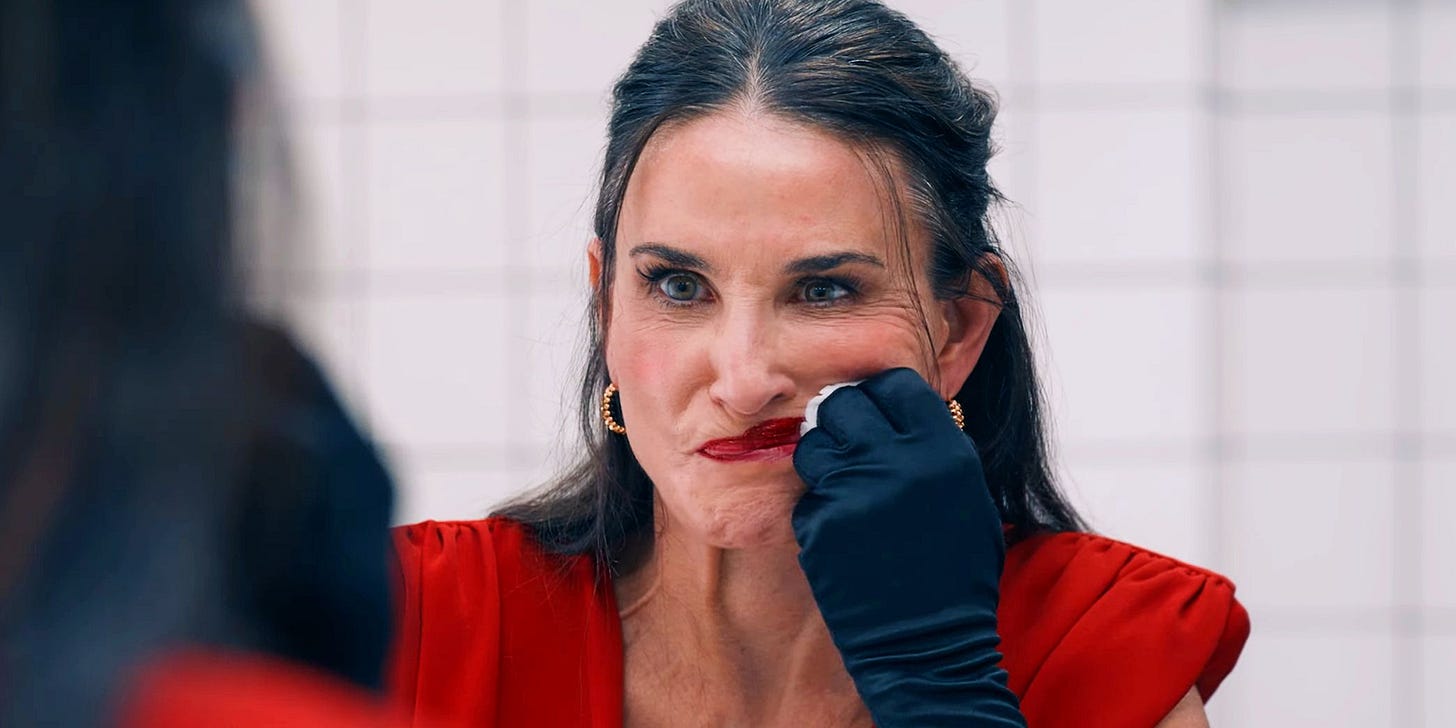

The Substance stars Demi Moore as Elisabeth Sparkle, the host of a popular morning aerobics show. No sooner does Elisabeth turn 50, however, than she’s fired by the network, overseen by a sleazy, gluttonous executive aptly named Harvey (Dennis Quaid). Elisabeth is understandably distraught… until she catches wind of the Substance, a chemical injection that promises to produce a younger version of herself.

The non-vaginal birth of that younger self, Sue (Margaret Qualley), is the first - and perhaps mildest - of The Substance’s myriad of thoroughly icky set pieces. Sue and Elisabeth can’t co-exist, so they’re given a set of rules to follow to maintain “balance.” One of them ostensibly gets to live her life for seven days while the other one is in something akin to a coma, and then they switch. When it’s Elisabeth’s “turn” to live, all she really has to do is keep Sue’s intravenous food supply stocked; but when Sue is “awake,” she has to take a “stabilizer” injection extracted from Elisabeth’s spinal fluid on a daily basis.

Except after Sue lands Elisabeth’s old job and is launched into stardom, she’s increasingly unwilling to share her proverbial air time, opting instead to keep Elisabeth in her sedated state while constantly draining her of the “stabilizer” solution. Needless to say, this leads to perilous and often nauseating physical consequences. More insightfully, it also highlights the ways that unrealistic standards are a double-edged sword: Sue may be a literal part of Elisabeth, but the more the younger woman gets what she wants, the more the older woman hates herself. The enigmatic, never-seen administrators of the Substance keep trying to remind Elisabeth and Sue that they’re one person - but they never actually see each other that way. Elisabeth/Sue is, in the bluntest of terms, a character suffering from a severe lack of self-love.

The Substance unfolds with fairy tale-like simplicity and a confrontational sneer: its characters are hardly multi-dimensional and its meaning is about as subtle as colon cancer. Like many of the influences she wears on her sleeve, Fargeat is more interested in philosophical conundrums and visual semiotics than sentimentality or the intricacies of the human experience. She references other films and texts overtly and often: The Fly ‘86, The Shining, The Picture of Dorian Gray. But these allusions are more than mere intellectual peacocking; they’re always relevant to the larger thematics of Fargeat’s story. When Fargeat quotes 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s because she’s talking about evolution; when she quotes Requiem for a Dream, it’s because she’s talking about addiction; when she quotes Carrie, it’s because she’s talking about how women are judged and the destructive consequences of that judgment.

This is not to suggest that Fargeat lacks imagination. Like De Palma or Quentin Tarantino, she is remixing, not remaking, other creators’ material. It’s telling that so many of her inspirations were authored by men; Fargeat often seems to be calling attention to the microaggressions inherent in male-dominated storytelling. Why is Jack Torrance realizing he’s kissing not a beautiful young woman but a desiccated old witch so disturbing? Why does Seth Brundle find so much power in his virility? Can De Palma sincerely shame us for ogling Carrie White when his film opens with such a detailed study of her nude body? I don’t think Fargeat is necessarily shaming these films, but I do think she wants us to consider them in a slightly different way than we normally do.

At the center of all this cerebral mayhem is Moore, who has never been better. Don’t get me wrong: Quaid is appropriately cast, and the consistently excellent Qualley continues to do top-notch work. But Elisabeth truly allows Moore to strut; the character may not be deep, but she certainly has a wider range of feelings. There’s a sequence that is unsettling despite being considerably less graphic than the rest of the movie, in which Elisabeth is just trying to prepare for a date, and holy moly, does it ever turn into an emotional roller coaster. And it all comes down to Moore looking in a mirror (in fact, much of The Substance is executed with a bare minimum of dialogue, which won’t surprise anyone familiar with Fargeat’s 2017 feature debut, Revenge, which is a very different kind of feminist horror film). Between Moore in The Substance, Willa Fitzgerald in Strange Darling, and Kathryn Hunter in The Front Room, this is turning out to be an incredible time for female performers in horror films, and they all deserve as much recognition as the world can foist upon them.

As I come to the end of this recommendation, I feel as though I have perhaps undersold The Substance’s level of satire: the movie may very well make you toss your cookies, but if you’re willing to give in to its extremities, it will also make you guffaw. Rarely is a film this upsetting also so damn hilarious. The Substance is a very special picture, and I hope as many people see it as can stomach it.