Why is 'Late Night With the Devil' a Found Footage Film?

The indie horror film breaks with conventions of the genre - but why?

Late Night with the Devil is the new indie found-footage horror film that did surprisingly well at the box office this weekend following critical raves and some undue controversy that honestly probably helped more than it hurt.

Having now seen the film, I can confirm that it’s quite good! It’s really nice to see American goddamn treasure David Dastmalchian get the lead role for a change, there’s some fun gore (some of which I believe is practical?), and while the story is nothing you haven’t seen before, it’s well-executed enough to be a fun watch.

But I did walk away from Late Night with the Devil with one major question:

Why is this a found footage film?

Written and directed by Australian brothers Cameron & Colin Cairnes, the premise of Late Night with the Devil is that it’s a faux-documentary. It begins with a brief expository prologue, narrated by the inimitable Michael Ironside, in which we learn all about Jack Dorsey (Dastmalchian), the host of a (fictional) late night talkshow, Night Owls. During the 1970s, Jack, we’re told, came close to overthrowing Johnny Carson in the ratings, but never quite pulled it off; in fact, as the decade continued, Jack’s popularity with viewers began to flag.

Adding to Jack’s woes: in 1976, his wife, a Broadway star named Madeline (Georgina Haig), died from lung cancer, despite having never smoked a day in her life. Everything came to a head the following year: with his contract up for renewal, Jack desperately engaged in increasingly-provocative on-air stunts, none of which ever managed to put him over the top…

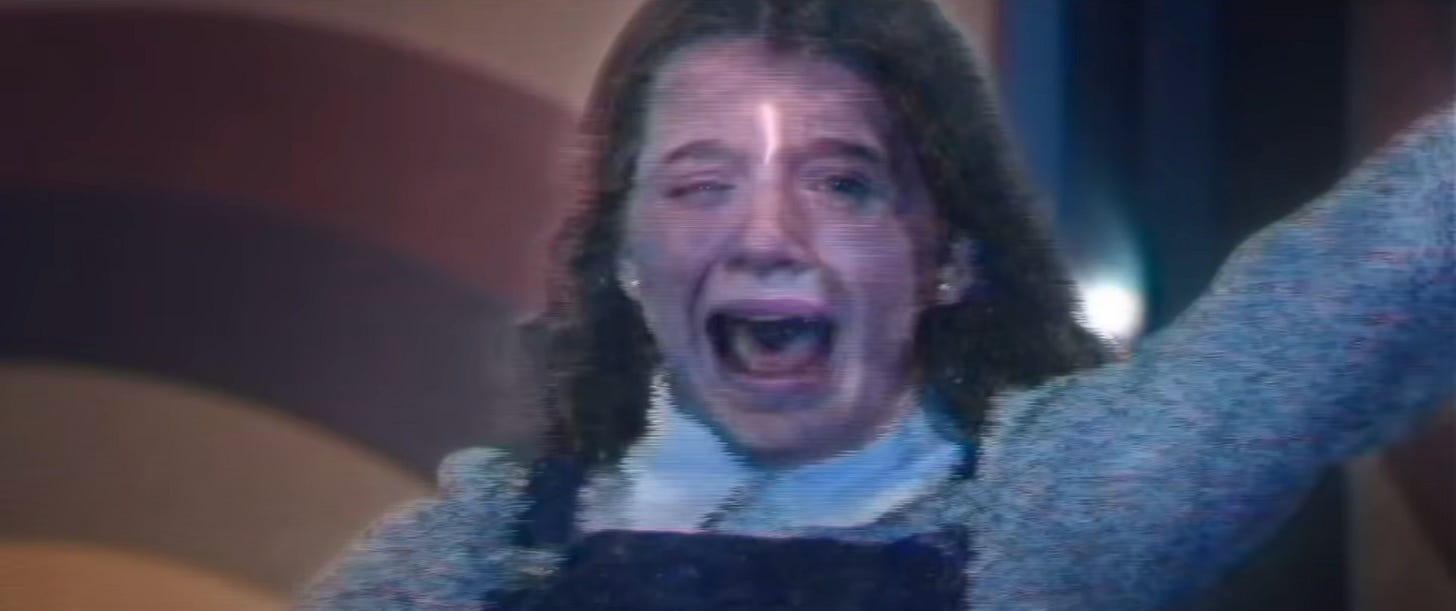

…until the last-ever episode of Night Owls, which aired on Halloween night, 1977, and featured as its primary guest Lilly (Ingrid Torelli), a young girl allegedly suffering from demonic possession after being rescued from a Satanic cult. The episode, the narrator asserts, “shocked the nation” - but the master tape was long thought lost. Most of Late of Night with the Devil consists of this unearthed master tape. In addition to the episode itself, the narrator tells us, we’re going to get view never-before-seen backstage footage filmed during commercial breaks (differentiated by being shot in black and white).

Thing is, found footage horror movies really only work as “found footage” if they’re verisimilitudinous. Remember, some people initially thought The Blair Witch Project was real! The BBC’s Ghostwatch, which debuted Halloween night, 1992, also fooled quite a few viewers. Another great found footage movie about an alleged television broadcast from Halloween night several decades prior, 2013’s WNUF Halloween Special, mimics actual local American news shows from the 1980s from that era such incredible accuracy it includes commercials you’ll have a hard time believing were never real.

But Late Night with the Devil is never convincing in this regard: it plays like Frost/Nixon or Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip if either of those were inexplicably presented in the found footage format.

Never mind that we all know there was never a show called Night Owls with Jack Dorsey, and never mind that Dastmalchian, having recently become one of the industry’s most in-demand character actors, is an instantly-recognizable face (you’ve seen him in mega-blockbusters like Oppenheimer, Dune, Ant-Man, and The Suicide Squad, amongst many others). Even if these things were not true, there would be a number of ways in Late Night with the Devil betrays its own gimmick.

The behind-the-scenes footage is shot and edited like a regular film, with close-ups and reaction shots and cutaways and all the fixings. This would only be possible if there were multiple cameras backstage all conveniently filming different angles at once - so the viewer immediately knows this isn’t documentary footage.

Even putting THAT aside, other than the 4:3 aspect ratio of the unfolding Night Owls episode, the Cairnes brothers only just-barely stick to the aesthetic of an American talk show in the late-‘70s. There are simply too many moments when the camera very smoothly repositions or slowly zooms in on the exact right person, as though the cameraman had the script and knew what was about to happen. It’s more subtle than the patently fake backstage scenes, but I guarantee that your brain will notice, if only on an unconscious level.

AND even putting THAT aside, if the things that happen in this movie happened on live television, in front of a studio audience no less, it would be a HUGE deal, not something everyone forgot about until the master tapes were re-discovered fifty years later. These events are not ambiguously supernatural occurrences experienced by a very small group of people, like in Blair Witch… they’re nationally televised, inarguably abnormal, and would create a fairly major ripple effect throughout the world (even saying they “shocked the nation” seems to be understating it).

AND even putting THAT aside, the performances are all just a little too exaggerated to ever feel real; everyone in this film needs to be at like a four or a five on the acting dial, and they’re all at a solid seven. As a consequence, the movie more closely resembles a filmed broadcast of a play than footage from a real event (indeed, I thought more than once that Late Night with the Devil truly would make a pretty good play).

This isn’t a criticism of the cast: we know, for example, that Dastmalchian is insanely-talented (and the rest of the cast, which includes Laura Gordon, a.k.a. the woman who so disturbingly hyperventilated before being decapitated in Saw V, is also quite good). The fact that every actor across the board is overdoing things a little bit suggests that this was a conscious creative decision on the part of the brothers Cairnes.

And I’m not criticizing them, either. I don’t think these guys are stupid. They deliberately made a found footage movie, and not just a movie that happens to take place in a television studio in 1977. If this is how they wanted their movie to be, they surely had some kind of reasoning behind the decision.

What could that reasoning be?

I think it’s going to take at least one more viewing of the film for me to solidify my thesis, but here’s my theory after seeing it once.

SPOILERS AHEAD

I’m not entirely sure that Night Owls is, strictly speaking, ever supposed be an actual found footage film.

That may sound confusing, so let’s back up for a second.

First of all, there is more than a little bit of political subtext to Late Night with the Devil.

Some of it goes by pretty quickly: the prologue includes footage of the Vietnam war and news reports on the Watergate scandal, and during his opening monologue on Night Owls, Jack cracks wise about Jimmy Carter (who would have been winding down his first year in office at this time), mocking Carter as an “easy target” or “low-hanging fruit” or something to that effect (I forget the exactly line).

Meanwhile, the song which plays over the closing credits is Flo & Eddie’s “Keep It Warm,” first released in 1976. The track is parody of the Beach Boys, whose most famous songs are usually about recreational matters (“Keep It Warm” literally includes a piece of “Good Vibrations”). But unlike your average Beach Boys tune, the lyrics to “Keep It Warm” are all about prioritizing capitalism over art and the shortcomings of American politics (although what Jefferson Airplane singer Grace Slick has to do with anything is over my head):

Write another song for the money

Something they can sing, not so funny

Money in the bank to keep us warmElect another jerk to the White House

Gracie Slick is losing her Dormouse

Take her off the streets and keep her warm

Fight another war if they make you

Squeal on a friend or they'll take you

The future's in your lap, so keep it warm

The credits over which this song plays, by the way, are the same font and red, white, and blue color scheme of the credits for The Killing of America, a 1981 documentary that the filmmakers profess was a big influence on Late Night with the Devil. Cameron Cairnes describes the doc as “basically video footage of all these assassins and serial killers.”

Then there are the film’s references to an exclusive retreat, The Grove. This is clearly modeled on Bohemian Grove, the private Northern California campground which, per Vanity Fair, “Conspiracy theorists believe… are host to right-wing, old-boy machinations about the New World Order” (for the record, I think the conspiracy theories are hokum, but they do make for a good story, especially within the context of a horror narrative).

Probably not-coincidentally, the film completely breaks from the found footage form near its conclusion. Lilly levitates in the air, her head split open, her entire appearance sometimes glitching she was herself an old television monitor (which is itself a telling image that directly links evil to mass media).

As Lilly (or whatever is possessing Lilly) violently murder everyone in her immediate vicinity, Jack seems to escape. But then, abruptly, the aspect ratio changes, and we’re definitely not watching found footage anymore; we’re watching Jack’s subjective experience as he suffers through a nightmarish déjà vu of key moments from previous episodes of Night Owls…

…as well as his visit to Bohemian Grove (excuse me, “The Grove”). We learn that Jack made deal with the Devil to make him rich and famous; we also learn that the leader of the Satanic cult from which Lilly was rescued oversaw the ritual in which Jack participated. What Jack didn’t realize at the time, of course, is that Madeline’s life was part of that deal. Y’know. Fairly standard Faust/monkey’s paw/Wishmaster stuff.

This extended flashback/hallucination ends with Jack using a sacrificial knife from the Grove ceremony to put Madeline out of her misery (at her request)… except that as soon as he sinks the knife into her chest, the aspect ratio shifts again, and Jack is back on the set of Night Owls, where he is surrounded by dead bodies. To his horror, these include Lilly, cradled in his arms, the knife protruding from her heart - Jack may have thought he was stabbing his wife, but he was actually stabbing this poor young girl. The camera then cranes up and dreamily drifts away from Jack, and once again, the movie seems to deliberately abandon any claim to being found footage (for, surely, no camera person would have remained in the studio at this point, and certainly no one would have been operating a camera crane).

There’s a clear intersection, then, of the themes of greed and mass media. In fact, I’d argue that there is not a single character in the film who prioritizes Lilly’s well-being over their own success. The program’s beleaguered sidekick, Gus (Rhys Auteri), threatens to walk off the show, but backs down as soon as the producer (Josh Quong Tart) gets testy with him. The professional skeptic who is also a guest, Carmichael Haig (Ian Bliss), is more interested in disproving the existence of supernatural entities than what may actually happen to any of the people involved in this experience (and not for nothing, but he’s bet a hefty sum that he can, indeed, logically explain everything that happens). Even Lilly’s caretaker, June (Gordon), has a) written a book about her experiences with Lilly, and b) caves in to Jack’s demands to keep the show going, at least in part because Jack says it will help book sales (not mention that he’s her lover).

All of this, combined the movie playing it so fast and loose with the conventions of the found footage genre, kinda makes me think what we’ve been watching all along is, in fact, Jack’s personal Hell. Late Night with the Devil isn’t a found footage film posing as a documentary - it’s Jack’s memories of his tragic fate as the documentary he imagines will be his ultimate legacy. He wanted to be famous? Well, he’s famous: people will watch Late Night with the Devil for years to come.

Now, that might be too literal of an interpretation. Late Night with the Devil may not have a concrete “answer” - it may be more of an impressionistic/surrealist David Lynch-type-story. As I said, I think this movie will ultimately reward multiple viewings; I believe there are important details that I didn’t clock completely (the running metaphors of masks and hypnosis amongst them) and probably either bolster or detract from theory.

Whatever the case may be, it’s been a hot minute since I spent so much time thinking about a horror film. That Late Night with the Devil claimed so much real estate in my consciousness is, in and of itself, evidence that it’s a very good movie. I’ll be curious to revisit it at some point down the line.

Great writeup.

You give the movie makers too much credit. I think this was just a mess of a Ghost Watch UK rip off that shot its wad in ways Ghost Watch much more effectively delivered by pulling punches at key moments and the finale.

GW's creators knew the point wasn't to show gore and violence because the real power is the suggestion of evil and the creepiness of the unfolding evil. They were taking their lessons from Nigel Kneale's The Stone Tape, a movie you definitely need to see to get to the core of what inspired GW and then in a tertiary way, Devil.

Meanwhile, Devil's creators seem to have just lost their minds at the end and wrapped things up by showing the unlikable host character being tortured. I never cared about his arc because it was basically just a wordy exposition at the start and then a forgettable dream sequence at the end. Dreamer, here! Change the channel!