The Class of 1999: 'American Beauty'

This movie has aged about as well as a corpse left out in the sun.

1999 was a historically great year for film and dramatic narrative as a whole. I’m using my 2024 to look back at, reconsider, and celebrate these stories as they all celebrate their 25th anniversaries. I recently re-reviewed Beau Travail; next up on the docket is Three Kings. But first… it’s time for…

American Beauty - directed by Sam Mendes - written by Alan Ball - September 17, 1999

There are a few films that I was ambivalent about including or excluding from this retrospective. Did I need to cover The Phantom Menace even though it’s been written about ad nauseam for the past 25 years? Its failings as a film and importance as a cultural artifact have been pretty well covered.

So I skipped it.

Then there’s American Beauty.

The debut film by acclaimed theater director Sam Mendes, American Beauty has aged about as well as a corpse left out in the sun.

The parallels between the behavior of Kevin Spacey’s character in the film and Kevin Spacey’s alleged real-life crimes don’t do American Beauty any favors, especially since the movie is oddly non-judgmental about a middle-aged man trying to fuck a high school student.

But even if American Beauty starred someone with a less problematic history than Spacey, it wouldn’t be a very good movie. It’s a trite, lowest-common-denominator pseudo-intellectualist sitcom episode with above-average production values… which isn’t all that surprising given that it was first produced screenplay by Alan Ball, who had previously been employed on sitcoms like Grace Under Fire and Cybil (after American Beauty, he went on to create the HBO hits Six Feet Under and True Blood). I completely understand why an 11-year-old who has never seen a movie before might perceive it as being profound, but thinking adults ought to find it stupid, boring, and kind of repulsive.

It grossed $356 million worldwide on a budget of just $15 million and won five Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay, and Best Actor.

American Beauty is about a supposedly-typical middle-class suburban man, Lester Burnham (Spacey), who narrates the story from beyond the grave1. His wife, an ambitious real estate agent named Carolyn (Annette Bening), and his adolescent daughter, Jane (Thora Birch), both hate him and treat him like shit. He learns that he’s about to get laid off from his soulless corporate job after fifteen years. He does not appear to have any real friends. His life sucks, and he is, by his own admission, just kind of sleepwalking through it.

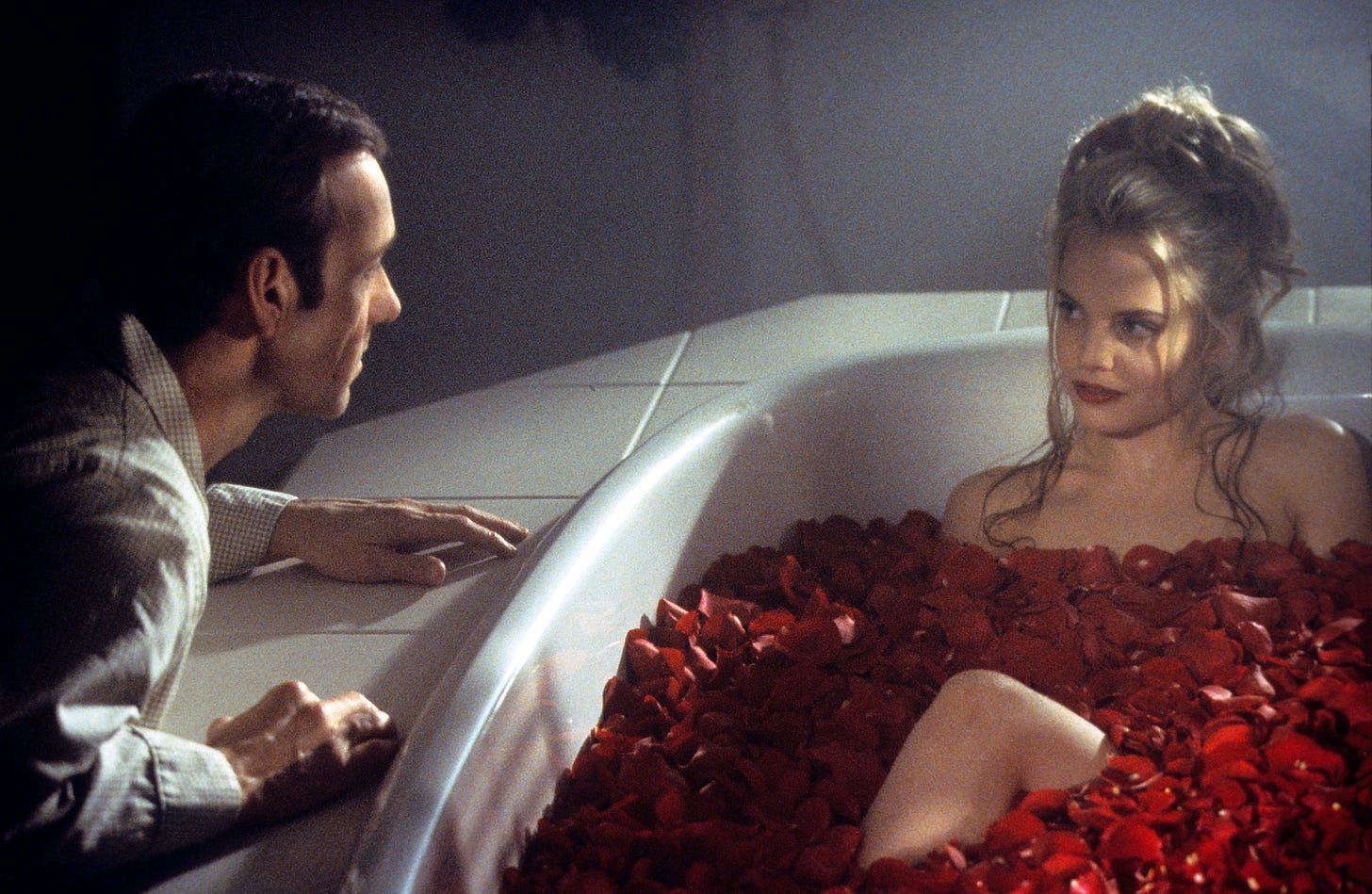

What wakes Lester up, unfortunately, is meeting his daughter’s fellow cheerleader, Angela Hayes (Mena Suvari). His newfound desire to screw a 17-year-old causes Lester to pull a complete one-eighty: he blackmails his boss into giving him a more-than-generous severance package, gets a new job at a fast food joint, starts working out with his gay neighbors (Scott Bakula and Sam Robards), and buys weed from Ricky Fitts (Wes Bentley), the strange teenager who just moved in next door with his ex-military father (Chris Cooper) and seemingly shellshocked mother (Allison Janney).

Carolyn, meanwhile, begins an affair with another local real estate agent, Buddy Kane (Peter Gallagher), while Ricky wins over Jane by peeping on her (because that’s something that all women love, right?)2.

Ricky and Jane ultimately make plans to run away together, but don’t manage to do so before the extremely homophobic Colonel Fitts comes to believe that Ricky is sleeping with Lester. When Colonel Fitts makes a pass at Lester, we come to realize that Ricky’s dad is a closeted homosexual, and his homophobia is a form of self-loathing. He runs off, humiliated.

Lester finally gets the opportunity to sleep with Angela, but when she confesses that she’s a virgin, he realizes what a mistake he’s making. He seems poised to try and make his peace with Carolyn and Jane, who he loves despite everything; unfortunately, Colonel Fitts can’t live with Lester’s rejection, and thus shoots Lester in the back of the head.

The end.

Before I truly tear American Beauty a new asshole, let’s pause to make fun of the film’s aesthetic mediocrity.

I’ve already spoken at length about American Beauty’s visual shortcomings3. I don’t want to belabor the point too much. But I do want to belabor the point a little.

Watch these two scenes of Lester and his family having dinner. The first scene takes place early in the movie, before Lester meets Angela; the second one comes later, after Lester quits his job.

Given that Lester is in a very different headspace in the second scene, one might assume that Mendes’ visual decisions would emphasize the contrast. And there are some divergences: the second has brighter lighting and more upbeat music, and Lester’s posture is completely different. Additionally, in the first dinner, Mendes (and editors Tariq Anwar and Christopher Greenbury) doesn’t cut to any close-ups until after Jane leaves in a huff, which makes the sequence feel a bit chillier, emotionally speaking.

But the framing is identical, and the camera only ever moves to keep an actor in the shot if they have to stand up or reach across the table or whatever. The most substantial difference between the two is that they shot basic coverage for the second scene. That was, like, Mendes’ big idea, I guess?

It’s not like it’s incompetent or anything… it’s just pedestrian (in the words of Brian De Palma, “Coverage is for cowards”). Mendes’ roots as a theater director are on full display. He’s not thinking cinematically, and the film suffers for it.

Also, that thing with the plastic bag? Yeah, it was stolen from from Nathaniel Dorsky’s 1998 silent experimental film, Variations. So. Fuck that, dude.

Now, with regards to the thematics of American Beauty…

Like so many movies from The Class of 1999, American Beauty is primarily about turn-of-the-century white collar malaise. Insofar as Mendes and Ball are concerned, there is one very, very simple solution for overcoming this angst: everyone needs to get laid.

Early in the film, we see Lester masturbating in the shower, which he calls “the best part of my day.” We soon learn that he and Carolyn never have sex anymore. Lester’s reawakening is a direct result of his lust for Angela.

Carolyn and Jane are each variations of a stereotype: the uptight woman who will loosen up as soon as they receive a good shtupping. Carolyn is made to seem bitchy from the moment we meet her, and when Lester tries to have sex with her, she becomes concerned that he’s going to spill beer on their living room couch (read: she’s frigid and has a stick up her ass); then, after the first time she sleeps with Buddy Kane, she literally says “That’s just what I needed.” Jane, meanwhile, is surly and sullen until she hooks up with Ricky.

Colonel Fitts’ entire reason for being an abusive prick is that he feels like he can’t fuck who he wants to fuck (i.e., other men); by extension, Mrs. Fitts’ entire reason for being so dazed and confused is that her husband won’t put out.

Yeah, the movie also acknowledges the ills of capitalism and the importance of love, but not in a pronounced way. Lester’s problem with working for a big faceless corporation isn’t that it’s a big faceless corporation, it’s that he’s afraid to stand up for himself. Lester comes to realize he loves Carolyn right at the end, maybe, kind of?, but it’s not like in Eyes Wide Shut, which explores the interconnection of love and lust; Lester doesn’t ultimately opt not to sleep with Angela because he realizes he loves Carolyn, but because he realizes Angela is just a child (which, like, duh).

I am in no way denying the importance of sex.

I’m saying American Beauty’s view of sex is overly simple and, to use the parlance of the day, weird.

Election plays its characters’ thoughtless lust for dark comedy, acknowledging how pathetic these people are; American Beauty starts out laughing at Lester, but it starts laughing with Lester as soon as meets Angela and starts behaving like an obnoxious teenager.

Office Space, The Matrix, and Fight Club all center around characters who don’t find love and sex until after they’ve shaken off the chains of capitalism; Lester can’t shake off those chains until after he gets a hard-on for a high schooler.

Virility, American Beauty tells us, is the key to everything.

There is a difference between portrayal and endorsement, of course. I do not believe, for example, that Vladimir Nabokov intended Lolita to be a celebration of pedophilia; or, to put it in more Class of ‘99 terms, I don’t think David Fincher’s hope was that domestic terrorist cells born from underground fight clubs would spring up around the country as a result of his film.

But if American Beauty sees Lester as a Humbert Humbert for the modern age, it sure does have an odd way of expressing it. Again: it is mostly laughing with Lester, not at Lester. His death is played as a horrible tragedy. And did I mention this movie has an issue with women? Or that Ball went on to make a movie about the sexual awakening of a 13-year-old girl, who is, at one point in the story, sexually assaulted by a 40-year-old man? Or that Birch was a minor when she filmed her topless scene? Suvari, who also appears nude in the film, wasn’t a minor at the time of production, but she wasn’t old enough to legally drink, either; I guess that, unlike the rest of Hollywood, Mendes couldn’t find a single actress over the age of 21 that could convincingly play a high schooler.

It’s the combined effect of these things - being blasé about Lester’s lust for a kid, getting an actual kid to do actual nudity for the film, and disseminating negative stereotypes about women, and this all being subject matter that apparently really interests Ball - that make me feel as though the makers of American Beauty are… well… if not condoning Lester, then certainly not condemning him, either (watch that second dinner scene again - does it feel to you as though the movie is coming down on Lester?).

The movie becomes even more troublesome when you start to think about its title and its cast.

In 1999, it was still reasonably progressive to show a happy, “normal” gay couple in a movie (Ball himself is gay), but it was also already noticeable when the entire population of a movie was White. In some instances, the lack of cast members of color was either for the sake of a pitiable reality (the characters in Election, The Virgin Suicides, and The Iron Giant probably wouldn’t know many Black people); in some instances, it was part of the point (as in Office Space and South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut, where the characters are explicitly chided for their racism); and in some instances, you could successfully argue that it was historically accurate, or that it was part of the point, or that the filmmakers were ignorant (Eyes Wide Shut).

There are minority actors in American Beauty… but they’re all background talent. I don’t think any of them have a single line. And this feels especially pernicious because the movie’s title is declarative: yeah, it refers to flowers, but what it’s really saying is that this story is a portrayal of American beauty. And that American beauty, apparently, doesn’t include anyone who’s not White.

American Beauty reassures those who benefit from hegemony that it’s not their fault their lives didn’t go the way they wanted.

Which, come to think of it, is probably why it was such a big hit.

The Class of 1999

Originally, the movie was framed by the trial of Lester’s daughter and her boyfriend, who have been wrongfully accused of murdering Lester; mercifully, that part of the movie was cut out before release, although remnants of it remain in the way the story hints that the young couple might kill Lester.

He also spells out her name in fire outside her window. But I buy a teenager finding destruction of public property in their honor to be romantic.

The film was shot by Conrad Hall, the legendary cinematographer for films such as Cool Hand Luke, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and Marathon Man; he won an Oscar for American Beauty, even though it’s not exactly his finest work.

Man, I can't believe I'm the only person here, but as someone who just rewatched this movie, I disagree, at least on your main point.

I think you're overly focused on Angela being the cause of Lester's change. I think that Lester's major point of change wasn't her, but Ricky, when Lester smoked weed with him behind the banquet. It was in that moment, Lester realized that he was embracing all the wrong things in his life, and went back to the last time he felt like he was legitimately his authentic self, which was when he was in high school/college. He decided to COMPLETELY live his life in that way, without regards for any of the consequences.

The problem with that was that it IS inappropriate for a 40-ish man to live like he's in high school. From that perspective, Angela was a symptom, not the cause, or his crisis. But, in a large way, this movie was a coming-of-age for a mid-life crisis, and for the majority of the film, he was a complete ass, but he makes progress throughout the film, and his almost having sex with Angela was what finally woke him up, both allowing him to embrace both what made him authentic, as well as the period of life he was in, instead of just what he wanted to be. In those last moments of the film, he honestly felt like a dad, both for Angela and Jane. On top of that, he also seemed like he understood how his wife wanted to grow, but that was less flushed out than his relationship with Jane.

Now, don't get me wrong, there's a lot problematic with the film, especially with how it sexualized teens. If the film were made today, it would probably have a much larger sleaze factor, but judging it compared to its contemporaries, I think the film was remarkably realistic and progressive with its portrayal of teens who were faking their sexual prowess, as well as Lester's recognizing that taking advantage of that as morally wrong. And, in a lot of ways, the film called Lester out on it, both via Jane and his wife.

Just my thoughts, having just finished the movie and looking for online analysises of it xD

You're trying to analyze an arty movie as if it's a solid mainstream sort of effort. I reflect that this is a movie that pretends to be something other than what it is. A great deal of what you take it to be strikes me as what it is pretending to be, superficially. Honestly I think you're rather smug in your analysis of the shot list as being 'He’s not thinking cinematically', I don't want to garble my point that I do simply disagree. This is a highly sophisticated movie, that operates on multiple levels. What is interesting about the movie is not any sort of 'message', at all -- it's not a 'message' movie.

For example, the title is 'American Beauty' and the message therefore is.. the title doesn't, though, actually mean much of anything. I realize the impression is 'it's so didactic', which isn't always a bad thing maybe, but isn't the thing here. One might figure quickly that 'the deck is so clearly stacked to make all these points', but that's only the first approximation of what the movie is up to, actually.

This movie did $350,000,000 ticket sales, and with confidence my guess is that the producers probably figured that $30,000,000 seemed optimistic. You have a speculation as to why the movie is such a big hit, of course -- something about 'hegemony', you lost me. I admit I simply think the word sounds dumb, you honestly lost me here.

You say 'Mrs. Fitts’ entire reason for being so dazed and confused is that her husband won’t put out.' Not true, I think -- no reason is given. It would be difficult for me to skip past the straightforward possibility here of dementia or Alzheimer’s. She forgot that her son doesn’t eat bacon. Telling him to wear a raincoat when he already had one on. Also, with a hypocritical, abusive, Marine-minded husband, there is more to consider than 'her husband won’t put out', which seems to be a reference to how her husband turns out to be a closeted homosexual, but skips right past how that wouldn't actually be directly an explanation of why her existence is ghostly and subservient.

Of course the colonel appears to have very strong ideals what it means to be a man and raises his son to believe in those same ideals -- cannot leave the military life behind. Strive -- to the point of break -- for perfection.

So, her existence -- I see a concept here of 'There is nothing ‘wrong’ with her, per se'. Looks like deep, mental scars, looks psychotically depressed. To me the image here is ambiguous, has something faded away? There is a contrast between her and other characters, like Carolyn is over ambitious. Angela has this fear of ultimately being ordinary. I would say that taking this or that idea, this or that character, you might see something fairly straightforward, not too interesting, but the juxtapositions make it interesting. A trash bag that is 'beautiful'? Not, in itself, so very interesting to me, but put it next to the girl who repeatedly says that nothing is worse than being ordinary. Angela is beautiful. The movie is about the internal conflict, such as 'homosexual and homophobic at the same time', which is not in itself an interesting idea, but more abstractly, we have a chance to compare and contrast these characters. What is 'disturbing' or 'uncomfortable' or just 'confusing' is where you find what pulls the movie together, which of course, is a movie that does grab almost everyone.

You pick up on a 'message' here, about how damaging and unhealthy suppressed sexual desires can be. But hold on, because also something forces people like Angela to boast of having had sex with many. She does not accept herself. All the characters pretty much feel the same, that "beauty" and "perfection" are the same thing. And this is true.

You could see the movie, apply yourself to parsing the 'message', and say 'this pretentious high school kid is some kind of secret emotional genius and has the whole world figured out'. Gimme a break...

Thus, how fast it became "hip" to crap all over this movie. I find it rather boring that people act like they are above it now. I'll save you the trouble if this is your reply: 'I've been sh*tting on this movie since it was released.' ;)

The way this story is weaved together is magnificent.